Introduction

Ixa (Interactive eXecution of ABMs) is a Rust framework for building modular agent-based discrete event models for large-scale simulations. While its primary application is modeling disease transmission, its flexible design makes it suitable for a wide range of simulation scenarios.

Ixa is named after the Ixa crab, a genus of Indo-Pacific pebble crabs from the family Leucosiidae.

You are reading The Ixa Book, a tutorial introduction to Ixa. API documentation can be found at https://ixa.rs/doc/ixa.

This book assumes you have a basic familiarity with the command line and at least some experience with programming.

Get Started

If you are new to Rust, we suggest taking some time to learn the parts of Rust that are most useful for ixa development. We've compiled some resources in rust-resources.md.

Execute the following commands to create a new Rust project called ixa_model.

cargo new --bin ixa_model

cd ixa_model

Use Ixa's new project setup script to setup the project for Ixa.

curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/CDCgov/ixa/main/scripts/setup_new_ixa_project.sh | sh -s

Open src/main.rs in your favorite editor or IDE to verify the model looks like

the following:

use ixa::run_with_args;

fn main() {

run_with_args(|context, _, _| {

context.add_plan(1.0, |context| {

println!("The current time is {}", context.get_current_time());

});

Ok(())

})

.unwrap();

}To run the model:

cargo run

# The current time is 1

To run with logging enabled globally:

cargo run -- --log-level=trace

To run with logging enabled for just ixa_model:

cargo run -- --log-level=ixa_model:trace

Command Line Usage

This document contains the help content for the ixa command-line program.

ixa

Default cli arguments for ixa runner

Usage: ixa [OPTIONS]

Options:

-

-r,--random-seed <RANDOM_SEED>— Random seedDefault value:

0 -

-c,--config— Optional path for a global properties config file -

-o,--output <OUTPUT_DIR>— Optional path for report output -

--prefix <FILE_PREFIX>— Optional prefix for report files -

-f,--force-overwrite— Overwrite existing report files? -

-l,--log-level <LOG_LEVEL>— Enable logging -

-v,--verbose— Increase logging verbosity (-v, -vv, -vvv, etc.)Level ERROR WARN INFO DEBUG TRACE Default ✓ -v ✓ ✓ ✓ -vv ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ -vvv ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ -

--warn— Set logging to WARN level. Shortcut for--log-level warn -

--debug— Set logging to DEBUG level. Shortcut for--log-level DEBUG -

--trace— Set logging to TRACE level. Shortcut for--log-level TRACE -

-d,--debugger— Set a breakpoint at a given time and start the debugger. Defaults to t=0.0 -

-w,--web— Enable the Web API at a given time. Defaults to t=0.0 -

-t,--timeline-progress-max <TIMELINE_PROGRESS_MAX>— Enable the timeline progress bar with a maximum time -

--no-stats— Suppresses the printout of summary statistics at the end of the simulation

Your First Model

In this section we will get acquainted with the basic features of Ixa by implementing a simple infectious disease transmission model. This section is just a starting point. It is not intended to be:

- An introduction to the Rust programming language (or crash course) or software engineering topics like source control with Git

- A tutorial on using a Unix-flavored command line

- An overview or survey of either disease modeling or agent-based modeling

- An exhaustive treatment of all of the features of Ixa

Our Abstract Model

We introduce modeling in Ixa by implementing a simple model for a food-borne illness where infection events follow a Poisson process. We assume that each susceptible person has a constant risk of becoming infected over time, independent of past infections. The Poisson process describes events (infections) occurring randomly in time but with a constant rate.

In this model, each individual susceptible person has an exponentially distributed time until they are infected. This means the time between successive infection events follows an exponential distribution. The rate of infection is typically expressed as a force of infection, which is a measure of the risk of a susceptible individual contracting the disease. In the case of a food-borne illness, this force is constant, meaning each susceptible individual faces a fixed probability per unit time of becoming infected, independent of the number of people already infected. Infected individuals subsequently recovery and cannot be re-infected. (Note that while this model has S, I, and R compartments, it is different from the canonical "SIR" model. In our simple model, the force of infection does not depend on the prevalence of infected persons. Put another way, our "I" compartment consists merely of infected persons; they are not infectious.)

High-level view of how Ixa functions

This diagram gives a high-level view of how Ixa works:

Don't expect to understand everything in this diagram straight away. The major concepts we need to understand about models in Ixa are:

Context: AContextkeeps track of the state of the world for our model and is the primary way code interacts with anything in the running model.- Timeline: A future event list of the simulation, the timeline is a queue

of

Callbackobjects -called plans - that will assume control of theContextat a future point in time and execute the logic in the plan. - Plan: A piece of logic scheduled to execute at a certain time on the

timeline. Plans are added to the timeline through the

Context. - Agents: Generally people in a disease model, agents are the entities that dynamically interact over the course of the simulation. Data can be associated with agents as properties—"people properties" in our case.

- Property: Data attached to an agent.

- Module: An organizational unit of functionality. Simulations are

constructed out of a series of interacting modules that take turns

manipulating the Context through a mutable reference. Modules store data in

the simulation using the

DataPlugintrait that allows them to retrieve data by type. - Event: Modules can also emit 'events' that other modules can subscribe to handle by event type. This allows modules to broadcast that specific things have occurred and have other modules take turns reacting to these occurrences. An example of an event might be a person becoming infected by a disease.

The organization of a model's implementation

A model in Ixa is a computer program written in the Rust programming language that uses the Ixa library (or "crate" in the language of Rust). A model is organized into of a set of modules that work together to provide all of the functions of the simulation. For instance, a simple disease transmission model might consist of the following modules:

- A population loader that initializes the set of people represented by the simulation.

- A transmission manager that models the process of how a susceptible person in the population becomes infected.

- An infection manager that transitions infected people through stages of disease until recovery.

- A reporting module that records data about how the disease evolves through the population to a file for later analysis.

The single responsibility principle in software engineering is a key idea behind modularity. It states that each module should have one clear purpose or responsibility. By designing each module to perform a single task (for example, loading the population data, managing the transmission of the disease, or handling infection progression), you create a system where each part is easier to understand, test, and maintain. This not only helps prevent errors but also allows us to iterate and improve each component independently.

In the context of our disease transmission model:

- The population loader is solely responsible for setting up the initial state of the simulation by importing and structuring the data about people.

- The transmission manager focuses exclusively on modeling the process by which persons get infected.

- The infection manager takes care of the progression of the disease within an infected individual until recovery.

- The reporting module handles data collection and output, ensuring that results are recorded accurately.

By organizing the model into these distinct modules, each with a single responsibility, we ensure that our simulation remains organized and manageable—even as the complexity of the model grows.

The rest of this chapter develops each of the modules of our model one-by-one.

Setting Up Your First Model

Create a new project with Cargo

Let's setup the bare bones skeleton of our first model. First decide where your

Ixa-related code is going to live on your computer. On my computer, that's the

Code directory in my home folder (or ~ for short). I will use my directory

structure for illustration purposes in this section. Just modify the commands

for wherever you chose to store your models.

Navigate to the directory you have chosen for your models and then use Cargoto

initialize a new Rust project called disease_model.

cd ~/Code

cargo new --bin disease_model

Cargo creates a directory named disease_model with a project skeleton for us.

Open the newly created disease_model directory in your favorite IDE, like

VSCode (free) or

RustRover.

🏠 home/

└── 🗂️ Code/

└── 🗂️ disease_model/

├── 🗂️ src/

│ └── 📄 main.rs

├── .gitignore

└── 📄 Cargo.toml

source control

The .gitignore file lists all the files and directories you don't want to

include in source control. For a Rust project you should at least have

target and Cargo.lock listed in the .gitignore. I also make a habit of

listing .vscode and .idea, the directories VS Code and JetBrains

respectively store IDE project settings.

cargo

Cargo is Rust's package manager and build system. It is a single tool that

plays the role of the multiple different tools you would use in other

languages, such as pip and poetry in the Python ecosystem. We use Cargo to

- install tools like ripgrep (

cargo install) - initialize new projects (

cargo newandcargo init) - add new project dependencies (

cargo add serde) - update dependency versions (

cargo update) - check the project's code for errors (

cargo check) - download and build the correct dependencies with the correct feature flags

(

cargo build) - build the project's targets, including examples and tests (

cargo build) - generate documentation (

cargo doc) - run tests and benchmarks (

cargo test,cargo bench)

Setup Dependencies and Cargo.toml

Ixa comes with a convenience script for setting up new Ixa projects. Change

directory to disease_model/, the project root, and run this command.

curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/CDCgov/ixa/release/scripts/setup_new_ixa_project.sh | sh -s

The script adds the Ixa library as a project dependency and provides you with a

minimal Ixa program in src/main.rs.

Dependencies

We will depend on a few external libraries in addition to Ixa. The cargo add

command makes this easy.

cargo add rand_distr@0.4.3

cargo add csv

Notice that:

- a particular version can be specified with the

packagename@1.2.3syntax; - we can compile a library with specific features turn on or off.

Cargo.toml

Cargo stores information about these dependencies in the Cargo.toml file. This

file also stores metadata about your project used when publishing your project

to Crates.io. Even though we won't be publishing the crate to Crates.io, it's a

good idea to get into the habit of adding at least the author(s) and a brief

description of the project.

# Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "disease_model"

description = "A basic disease model using the Ixa agent-based modeling framework"

authors = ["John Doe <jdoe@example.com>"]

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

publish = false # Do not publish to the Crates.io registry

[dependencies]

csv = "1.3.1"

ixa = { git = "https://github.com/CDCgov/ixa", branch = "main" }

rand_distr = "0.5.1"

serde = { version = "1.0.217", features = ["derive"] }

Executing the Ixa model

We are almost ready to execute our first model. Edit src/main.rs to look like

this:

// main.rs

use ixa::run_with_args;

fn main() {

run_with_args(|context, _, _| {

context.add_plan(1.0, |context| {

println!("The current time is {}", context.get_current_time());

});

Ok(())

})

.unwrap();

}Don't let this code intimidate you—it's really quite simple. The first line says

we want to use symbols from the ixa library in the code that follows. In

main(), the first thing we do is call run_with_args(). The run_with_args()

function takes as an argument a closure inside which we can do additional setup

before the simulation is kicked off if necessary. The only setup we do is

schedule a plan at time 1.0. The plan is itself another closure that prints the

current simulation time.

closures

A closure is a small, self-contained block of code that can be passed around and executed later. It can capture and use variables from its surrounding environment, which makes it useful for things like callbacks, event handlers, or any situation where you want to define some logic on the fly and run it at a later time. In simple terms, a closure is like a mini anonymous function.

The run_with_args() function does the following:

-

It sets up a

Contextobject for us, parsing and applying any command line arguments and initializing subsystems accordingly. AContextkeeps track of the state of the world for our model and is the primary way code interacts with anything in the running model. -

It executes our closure, passing it a mutable reference to

contextso we can do any additional setup. -

Finally, it kicks off the simulation by executing

context.execute(). Of course, our model doesn't actually do anything or even contain any data, socontext.execute()checks that there is no work to do and immediately returns.

If there is an error at any stage, run_with_args() will return an error

result. The Rust compiler will complain if we do not handle the returned result,

either by checking for the error or explicitly opting out of the check, which

encourages us to do the responsible thing: match result checks for the error.

We can build and run our model from the command line using Cargo:

cargo run

Enabling Logging

The model doesn't do anything yet—it doesn't even emit the log messages we included. We can turn those on to see what is happening inside our model during development with the following command line argument:

cargo run -- --log-level trace

This turns on messages emitted by Ixa itself, too. If you only want to see

messages emitted by disease_model, you can specify the module in addition to

the log level:

cargo run -- --log-level disease_model=trace

logging

The trace!, info!, and error! logging macros allow us to print messages

to the console, but they are much more powerful than a simple print statement.

With log messages, you can:

- Turn log messages on and off as needed.

- Enable only messages with a specified priority (for example, only warnings or higher).

- Filter messages to show only those emitted from a specific module, like the

peoplemodule we write in the next section.

See the logging documentation for more details.

command line arguments

The run_with_args() function takes care of handling any command line

arguments for us, which is why we don't just create a Context object and

call context.execute() ourselves. There are many arguments we can pass to

our model that affect what is output and where, debugging options,

configuration input, and so forth. See the command line documentation for more

details.

In the next section we will add people to our model.

The People Module

In Ixa we organize our models into modules each of which is responsible for a single aspect of the model.

modules

In fact, the code of Ixa itself is organized into modules in just the same way models are.

Ixa is a framework for developing agent-based models. In most of our models,

the agents will represent people. So let's create a module that is responsible

for people and their properties—the data that is attached to each person. Create

a new file in the src directory called people.rs.

Defining an Entity and Property

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use crate::POPULATION;

define_entity!(Person);

define_property!(

// The type of the property

enum InfectionStatus {

S,

I,

R,

},

// The entity the property is associated with

Person,

// The property's default value for newly created `Person` entities

default_const = InfectionStatus::S

);

/// Populates the "world" with the `POPULATION` number of people.

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing people");

for _ in 0..POPULATION {

let _: PersonId = context.add_entity(()).expect("failed to add person");

}

}We have to define the Person entity before we can associate properties with

it. The define_entity!(Person) macro invocation automatically defines the

Person type, implements the Entity trait for Person, and creates the type

alias PersonId = EntityId, which is the type we can use to represent

specific instances of our entity, a single person, in our simulation.

To each person we will associate a value of the enum (short for “enumeration”)

named InfectionStatus. An enum is a way to create a type that can be one of

several predefined values. Here, we have three values:

- S: Represents someone who is susceptible to infection.

- I: Represents someone who is currently infected.

- R: Represents someone who has recovered.

Each value in the enum corresponds to a stage in our simple model. The enum

value for a person's InfectionStatus property will refer to an individual’s

health status in our simulation.

The module's init() function

While not strictly enforced by Ixa, the general formula for an Ixa module is:

- "public" data types and functions

- "private" data types and functions

The init() function is how your module will insert any data into the context

and set up whatever initial conditions it requires before the simulation begins.

For our people module, the init() function just inserts people into the

Context.

/// Populates the "world" with people.

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing people");

for _ in 0..1000 {

let _: PersonId = context.add_entity(()).expect("failed to add person");

}

}The context.add_entity() method call might look a little odd, because we are

not giving context any data to insert, but that is because our one and only

Property was defined to have a default value of InfectionStatus::S

(susceptible)—so context.add_entity() doesn't need any information to create a

new person. Another odd thing is the .expect("failed to add person") method

call. In more complicated scenarios adding a person can fail. We could intercept

that failure if we wanted, but in this simple case we will just let the program

crash with a message about the reason: "failed to add person".

Finally, the Context::add_entity method returns an entity ID wrapped in a

Result, which the expect method unwraps. We can use this ID if we need to

refer to this newly created person. Since we don't need it, we assign the value

to the special "don't care" variable _ (underscore), which just throws the

value away. Why assign it to anything, though? So that the compiler can infer

that it is a Person we are creating, as opposed to some other entity we may

have defined. If we just omitted the let _: PersonId = part completely, we

would need to explicitly specify the entity type using

turbo fish notation.

Constants

Having "magic numbers" embedded in your code, such as the constant 1000 here

representing the total number of people in our model, is bad practice.

What if we want to change this value later? Will we even be able to find it in

all of our source code? Ixa has a formal mechanism for managing these kinds of

model parameters, but for now we will just define a "static constant" near the

top of src/main.rs named POPULATION and replace the literal 1000 with

POPULATION:

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use crate::POPULATION;

define_entity!(Person);

define_property!(

// The type of the property

enum InfectionStatus {

S,

I,

R,

},

// The entity the property is associated with

Person,

// The property's default value for newly created `Person` entities

default_const = InfectionStatus::S

);

/// Populates the "world" with the `POPULATION` number of people.

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing people");

for _ in 0..POPULATION {

let _: PersonId = context.add_entity(()).expect("failed to add person");

}

}Let's revisit src/main.rs:

mod incidence_report;

mod infection_manager;

mod people;

mod transmission_manager;

use ixa::{Context, error, info, run_with_args};

static POPULATION: u64 = 100;

static FORCE_OF_INFECTION: f64 = 0.1;

static MAX_TIME: f64 = 200.0;

static INFECTION_DURATION: f64 = 10.0;

fn main() {

let result = run_with_args(|context: &mut Context, _args, _| {

// Add a plan to shut down the simulation after `max_time`, regardless of

// what else is happening in the model.

context.add_plan(MAX_TIME, |context| {

context.shutdown();

});

people::init(context);

transmission_manager::init(context);

infection_manager::init(context);

incidence_report::init(context).expect("Failed to init incidence report");

Ok(())

});

match result {

Ok(_) => {

info!("Simulation finished executing");

}

Err(e) => {

error!("Simulation exited with error: {}", e);

}

}

}- Your IDE might have added the

mod people;line for you. If not, add it now. It tells the compiler that thepeoplemodule is attached to themainmodule (that is,main.rs). - We also need to declare our static constant for the total number of people.

- We need to initialize the people module.

Imports

Turning back to src/people.rs, your IDE might have been complaining to you

about not being able to find things "in this scope"—or, if you are lucky, your

IDE was smart enough to import the symbols you need at the top of the file

automatically. The issue is that the compiler needs to know where externally

defined items are coming from, so we need to have use statements at the top of

the file to import those items. Here is the complete src/people.rs file:

//people.rs

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use crate::POPULATION;

define_entity!(Person);

define_property!(

// The type of the property

enum InfectionStatus {

S,

I,

R,

},

// The entity the property is associated with

Person,

// The property's default value for newly created `Person` entities

default_const = InfectionStatus::S

);

/// Populates the "world" with the `POPULATION` number of people.

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing people");

for _ in 0..POPULATION {

let _: PersonId = context.add_entity(()).expect("failed to add person");

}

}The Transmission Manager

We call the module in charge of initiating new infections the transmission

manager. Create the file src/transmission_manager.rs and add

mod transmission_manager; to the top of src/main.rs right next to the

mod people; statement. We need to flesh out this skeleton.

// transmission_manager.rs

use ixa::Context;

fn attempt_infection(context: &mut Context) {

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing transmission manager");

}Constants

Recall our abstract model: We assume that each susceptible person has a constant

risk of becoming infected over time, independent of past infections, expressed

as a force of infection. Mathematically, this results in an exponentially

distributed duration between infection events. So we need to represent the

constant FORCE_OF_INFECTION and a random number source to sample exponentially

distributed random time durations.

We have already dealt with constants when we defined the constant POPULATION

in main.rs. Let's define FORCE_OF_INFECTION right next to it. We also cap

the simulation time to an arbitrarily large number, a good practice that

prevents the simulation from running forever in case we make a programming

error.

// main.rs

mod people;

mod transmission_manager;

use ixa::Context;

static POPULATION: u64 = 1000;

static FORCE_OF_INFECTION: f64 = 0.1;

static MAX_TIME: f64 = 200.0;

// ...the rest of the file...Infection Attempts

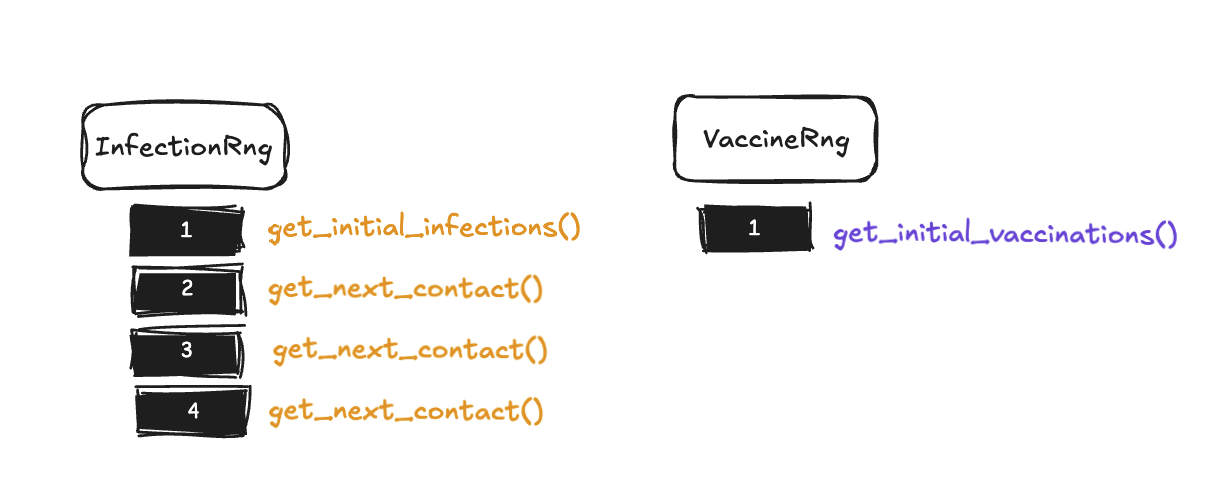

We need to import these constants into transmission_manager. To define a new

random number source in Ixa, we use define_rng!. There are other symbols from

Ixa we will need for the implementation of attempt_infection(). You can have

your IDE add these imports for you as you go, or you can add them yourself now.

// transmission_manager.rs

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use rand_distr::Exp;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, PersonId};

use crate::{FORCE_OF_INFECTION, POPULATION};

define_rng!(TransmissionRng);

fn attempt_infection(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Attempting infection");

let person_to_infect: PersonId = context.sample_entity(TransmissionRng, ()).unwrap();

let person_status: InfectionStatus = context.get_property(person_to_infect);

if person_status == InfectionStatus::S {

context.set_property(person_to_infect, InfectionStatus::I);

}

#[allow(clippy::cast_precision_loss)]

let next_attempt_time = context.get_current_time()

+ context.sample_distr(TransmissionRng, Exp::new(FORCE_OF_INFECTION).unwrap())

/ POPULATION as f64;

context.add_plan(next_attempt_time, attempt_infection);

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing transmission manager");

context.add_plan(0.0, attempt_infection);

}

// ...the rest of the file...The function attempt_infection() needs to do the following:

- Randomly sample a person from the population to attempt to infect.

- Check the sampled person's current

InfectionStatus, changing it to infected (InfectionStatus::I) if and only if the person is currently susceptible (InfectionStatus::S). - Schedule the next infection attempt by inserting a plan into the timeline

that will run

attempt_infection()again.

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use rand_distr::Exp;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, PersonId};

use crate::{FORCE_OF_INFECTION, POPULATION};

define_rng!(TransmissionRng);

fn attempt_infection(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Attempting infection");

let person_to_infect: PersonId = context.sample_entity(TransmissionRng, ()).unwrap();

let person_status: InfectionStatus = context.get_property(person_to_infect);

if person_status == InfectionStatus::S {

context.set_property(person_to_infect, InfectionStatus::I);

}

#[allow(clippy::cast_precision_loss)]

let next_attempt_time = context.get_current_time()

+ context.sample_distr(TransmissionRng, Exp::new(FORCE_OF_INFECTION).unwrap())

/ POPULATION as f64;

context.add_plan(next_attempt_time, attempt_infection);

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing transmission manager");

context.add_plan(0.0, attempt_infection);

}Read through this implementation and make sure you understand how it accomplishes the three tasks above. A few observations:

- The method call

context.sample_entity(TransmissionRng, ())takes the name of a random number source and a query and returns anOption<PersonId>, which can have the value ofSome(PersonId)orNone. In this case, we give it the "empty query"(), which means we want to sample from the entire population. The population will never be empty, so the result will never beNone, and so we just callunwrap()on theSome(PersonId)value to get thePersonId. - The

#[allow(clippy::cast_precision_loss)]is optional; without it the compiler will warn you about convertingpopulation's integral typeusizeto the floating point typef64, but we know that this conversion is safe to do in this context. - If the sampled person is not susceptible, then the only thing this function does is schedule the next attempt at infection.

- The time at which the next attempt is scheduled is sampled randomly from the

exponential distribution according to our abstract model and using the random

number source

TransmissionRngthat we defined specifically for this purpose. - None of this code refers to the people module (except to import the types

InfectionStatusandPersonId) or the infection manager we are about to write, demonstrating the software engineering principle of modularity.

random number generators

Each module generally defines its own random number source with define_rng!,

avoiding interfering with the random number sources used elsewhere in the

simulation in order to preserve determinism. In Monte Carlo simulations,

deterministic pseudorandom number sequences are desirable because they

ensure reproducibility, improve efficiency, provide control over randomness,

enable consistent statistical testing, and reduce the likelihood of bias or

error. These qualities are critical in scientific computing, optimization

problems, and simulations that require precise and verifiable results.

The Infection Manager

The infection manager (infection_manager.rs) is responsible for the evolution

of an infected person after they have been infected. In this simple model, there

is only one thing for the infection manager to do: schedule the time an infected

person recovers. We've already seen how to change a person's InfectionStatus

property and how to schedule plans on the timeline in the transmission module.

But how does the infection manager know about new infections?

Events

Modules can subscribe to events. The infection manager registers a function with Ixa that will be called in response to a change in a particular property.

// in infection_manager.rs

use ixa::prelude::*;

use rand_distr::Exp;

use crate::INFECTION_DURATION;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, Person, PersonId};

pub type InfectionStatusEvent = PropertyChangeEvent<Person, InfectionStatus>;

define_rng!(InfectionRng);

fn schedule_recovery(context: &mut Context, person_id: PersonId) {

trace!("Scheduling recovery");

let current_time = context.get_current_time();

let sampled_infection_duration =

context.sample_distr(InfectionRng, Exp::new(1.0 / INFECTION_DURATION).unwrap());

let recovery_time = current_time + sampled_infection_duration;

context.add_plan(recovery_time, move |context| {

context.set_property(person_id, InfectionStatus::R);

});

}

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Handling infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

if event.current == InfectionStatus::I {

schedule_recovery(context, event.entity_id);

}

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing infection_manager");

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

}This line isn't defining a new struct or even a new type. Rather, it defines an

alias for PropertyChangeEvent<E: Entity, P: Property<E>> with the generic

types instantiated for the property we want to monitor, InfectionStatus. This

is effectively the name of the event we subscribe to in the module's init()

function:

// in infection_manager.rs

use ixa::prelude::*;

use rand_distr::Exp;

use crate::INFECTION_DURATION;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, Person, PersonId};

pub type InfectionStatusEvent = PropertyChangeEvent<Person, InfectionStatus>;

define_rng!(InfectionRng);

fn schedule_recovery(context: &mut Context, person_id: PersonId) {

trace!("Scheduling recovery");

let current_time = context.get_current_time();

let sampled_infection_duration =

context.sample_distr(InfectionRng, Exp::new(1.0 / INFECTION_DURATION).unwrap());

let recovery_time = current_time + sampled_infection_duration;

context.add_plan(recovery_time, move |context| {

context.set_property(person_id, InfectionStatus::R);

});

}

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Handling infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

if event.current == InfectionStatus::I {

schedule_recovery(context, event.entity_id);

}

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing infection_manager");

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

}The event handler is just a regular Rust function that takes a Context and an

InfectionStatusEvent, the latter of which holds the PersonId of the person

whose InfectionStatus changed, the current InfectionStatus value, and the

previous InfectionStatus value.

// in infection_manager.rs

use ixa::prelude::*;

use rand_distr::Exp;

use crate::INFECTION_DURATION;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, Person, PersonId};

pub type InfectionStatusEvent = PropertyChangeEvent<Person, InfectionStatus>;

define_rng!(InfectionRng);

fn schedule_recovery(context: &mut Context, person_id: PersonId) {

trace!("Scheduling recovery");

let current_time = context.get_current_time();

let sampled_infection_duration =

context.sample_distr(InfectionRng, Exp::new(1.0 / INFECTION_DURATION).unwrap());

let recovery_time = current_time + sampled_infection_duration;

context.add_plan(recovery_time, move |context| {

context.set_property(person_id, InfectionStatus::R);

});

}

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Handling infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

if event.current == InfectionStatus::I {

schedule_recovery(context, event.entity_id);

}

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing infection_manager");

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

}We only care about new infections in this model.

Scheduling Recovery

As in attempt_infection(), we sample the recovery time from the exponential

distribution with mean INFECTION_DURATION, a constant we define in main.rs.

We define a random number source for this module's exclusive use with

define_rng!(InfectionRng) as we did before.

use ixa::prelude::*;

use rand_distr::Exp;

use crate::INFECTION_DURATION;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, Person, PersonId};

pub type InfectionStatusEvent = PropertyChangeEvent<Person, InfectionStatus>;

define_rng!(InfectionRng);

fn schedule_recovery(context: &mut Context, person_id: PersonId) {

trace!("Scheduling recovery");

let current_time = context.get_current_time();

let sampled_infection_duration =

context.sample_distr(InfectionRng, Exp::new(1.0 / INFECTION_DURATION).unwrap());

let recovery_time = current_time + sampled_infection_duration;

context.add_plan(recovery_time, move |context| {

context.set_property(person_id, InfectionStatus::R);

});

}

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Handling infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

if event.current == InfectionStatus::I {

schedule_recovery(context, event.entity_id);

}

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) {

trace!("Initializing infection_manager");

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

}Notice that the plan is again just a Rust function, but this time it takes the form of a closure rather than a traditionally defined function. This is convenient when the function is only a line or two.

closures and captured variables

The move keyword in the syntax for Rust closures instructs the closure to

take ownership of any variables it uses from its surrounding context—these are

known as captured variables. Normally, when a closure refers to variables

defined outside of its own body, it borrows them, which means it uses

references to those values. However, with move, the closure takes full

ownership by moving the variables into its own scope. This is especially

useful when the closure must outlive the current scope or be passed to another

thread, as it ensures that the closure has its own independent copy of the

data without relying on references that might become invalid.

The Incident Reporter

An agent-based model does not output an answer at the end of a simulation in the usual sense. Rather, the simulation evolves the state of the world over time. If we want to track that evolution for later analysis, it is up to us to collect the data we want to have. The built-in report feature makes it easy to record data to a CSV file during the simulation.

Our model will only have a single report that records the current in-simulation

time, the PersonId, and the InfectionStatus of a person whenever their

InfectionStatus changes. We define a struct representing a single row of data.

// in incidence_report.rs

use std::path::PathBuf;

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use serde::Serialize;

use crate::infection_manager::InfectionStatusEvent;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, PersonId};

#[derive(Serialize, Clone)]

struct IncidenceReportItem {

time: f64,

person_id: PersonId,

infection_status: InfectionStatus,

}

define_report!(IncidenceReportItem);

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Recording infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

context.send_report(IncidenceReportItem {

time: context.get_current_time(),

person_id: event.entity_id,

infection_status: event.current,

});

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) -> Result<(), IxaError> {

trace!("Initializing incidence_report");

// Output directory is relative to the directory with the Cargo.toml file.

let output_path = PathBuf::from(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"));

// In the configuration of report options below, we set `overwrite(true)`, which is not

// recommended for production code in order to prevent accidental data loss. It is set

// here so that newcomers won't have to deal with a confusing error while running

// examples.

context

.report_options()

.directory(output_path)

.overwrite(true);

context.add_report::<IncidenceReportItem>("incidence")?;

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

Ok(())

}The fact that IncidenceReportItem derives Serialize is what makes this magic

work. We define a report for this struct using the define_report! macro.

use std::path::PathBuf;

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use serde::Serialize;

use crate::infection_manager::InfectionStatusEvent;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, PersonId};

#[derive(Serialize, Clone)]

struct IncidenceReportItem {

time: f64,

person_id: PersonId,

infection_status: InfectionStatus,

}

define_report!(IncidenceReportItem);

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Recording infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

context.send_report(IncidenceReportItem {

time: context.get_current_time(),

person_id: event.entity_id,

infection_status: event.current,

});

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) -> Result<(), IxaError> {

trace!("Initializing incidence_report");

// Output directory is relative to the directory with the Cargo.toml file.

let output_path = PathBuf::from(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"));

// In the configuration of report options below, we set `overwrite(true)`, which is not

// recommended for production code in order to prevent accidental data loss. It is set

// here so that newcomers won't have to deal with a confusing error while running

// examples.

context

.report_options()

.directory(output_path)

.overwrite(true);

context.add_report::<IncidenceReportItem>("incidence")?;

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

Ok(())

}The way we listen to events is almost identical to how we did it in the

infection module. First let's make the event handler, that is, the callback

that will be called whenever an event is emitted.

use std::path::PathBuf;

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use serde::Serialize;

use crate::infection_manager::InfectionStatusEvent;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, PersonId};

#[derive(Serialize, Clone)]

struct IncidenceReportItem {

time: f64,

person_id: PersonId,

infection_status: InfectionStatus,

}

define_report!(IncidenceReportItem);

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Recording infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

context.send_report(IncidenceReportItem {

time: context.get_current_time(),

person_id: event.entity_id,

infection_status: event.current,

});

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) -> Result<(), IxaError> {

trace!("Initializing incidence_report");

// Output directory is relative to the directory with the Cargo.toml file.

let output_path = PathBuf::from(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"));

// In the configuration of report options below, we set `overwrite(true)`, which is not

// recommended for production code in order to prevent accidental data loss. It is set

// here so that newcomers won't have to deal with a confusing error while running

// examples.

context

.report_options()

.directory(output_path)

.overwrite(true);

context.add_report::<IncidenceReportItem>("incidence")?;

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

Ok(())

}Just pass a IncidenceReportItem to context.send_report()! We also emit a

trace log message so we can trace the execution of our model.

In the init() function there is a little bit of setup needed. Also, we can't

forget to register this callback to listen to InfectionStatusEvents.

use std::path::PathBuf;

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use serde::Serialize;

use crate::infection_manager::InfectionStatusEvent;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, PersonId};

#[derive(Serialize, Clone)]

struct IncidenceReportItem {

time: f64,

person_id: PersonId,

infection_status: InfectionStatus,

}

define_report!(IncidenceReportItem);

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Recording infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

context.send_report(IncidenceReportItem {

time: context.get_current_time(),

person_id: event.entity_id,

infection_status: event.current,

});

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) -> Result<(), IxaError> {

trace!("Initializing incidence_report");

// Output directory is relative to the directory with the Cargo.toml file.

let output_path = PathBuf::from(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"));

// In the configuration of report options below, we set `overwrite(true)`, which is not

// recommended for production code in order to prevent accidental data loss. It is set

// here so that newcomers won't have to deal with a confusing error while running

// examples.

context

.report_options()

.directory(output_path)

.overwrite(true);

context.add_report::<IncidenceReportItem>("incidence")?;

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

Ok(())

}Note that:

- the configuration you do on

context.report_options()applies to all reports attached to that context; - using

overwrite(true)is useful for debugging but potentially devastating for production; - this

init()function returns a result, which will be whatever error thatcontext.add_report()returns if the CSV file cannot be created for some reason, orOk(())otherwise.

result and handling errors

The Rust Result<U, V> type is an enum used for error handling. It

represents a value that can either be a successful outcome (Ok) containing a

value of type U, or an error (Err) containing a value of type V. Think

of it as a built-in way to return and propagate errors without relying on

exceptions, similar to using “Either” types or special error codes in other

languages.

The ? operator works with Result to simplify error handling. When you

append ? to a function call that returns a Result, it automatically checks

if the result is an Ok or an Err. If it’s Ok, the value is extracted; if

it’s an Err, the error is immediately returned from the enclosing function.

This helps keep your code concise and easy to read by reducing the need for

explicit error-checking logic.

If your IDE isn't capable of adding imports for you, the external symbols we need for this module are as follows.

use std::path::PathBuf;

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::trace;

use serde::Serialize;

use crate::infection_manager::InfectionStatusEvent;

use crate::people::{InfectionStatus, PersonId};

#[derive(Serialize, Clone)]

struct IncidenceReportItem {

time: f64,

person_id: PersonId,

infection_status: InfectionStatus,

}

define_report!(IncidenceReportItem);

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

trace!(

"Recording infection status change from {:?} to {:?} for {:?}",

event.previous, event.current, event.entity_id

);

context.send_report(IncidenceReportItem {

time: context.get_current_time(),

person_id: event.entity_id,

infection_status: event.current,

});

}

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) -> Result<(), IxaError> {

trace!("Initializing incidence_report");

// Output directory is relative to the directory with the Cargo.toml file.

let output_path = PathBuf::from(env!("CARGO_MANIFEST_DIR"));

// In the configuration of report options below, we set `overwrite(true)`, which is not

// recommended for production code in order to prevent accidental data loss. It is set

// here so that newcomers won't have to deal with a confusing error while running

// examples.

context

.report_options()

.directory(output_path)

.overwrite(true);

context.add_report::<IncidenceReportItem>("incidence")?;

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

Ok(())

}Next Steps

We have created several new modules. We need to make sure they are each

initialized with the Context before the simulation starts. Below is main.rs

in its entirety.

// main.rs

mod incidence_report;

mod infection_manager;

mod people;

mod transmission_manager;

use ixa::{Context, error, info, run_with_args};

static POPULATION: u64 = 100;

static FORCE_OF_INFECTION: f64 = 0.1;

static MAX_TIME: f64 = 200.0;

static INFECTION_DURATION: f64 = 10.0;

fn main() {

let result = run_with_args(|context: &mut Context, _args, _| {

// Add a plan to shut down the simulation after `max_time`, regardless of

// what else is happening in the model.

context.add_plan(MAX_TIME, |context| {

context.shutdown();

});

people::init(context);

transmission_manager::init(context);

infection_manager::init(context);

incidence_report::init(context).expect("Failed to init incidence report");

Ok(())

});

match result {

Ok(_) => {

info!("Simulation finished executing");

}

Err(e) => {

error!("Simulation exited with error: {}", e);

}

}

}Exercises:

- Currently the simulation runs until

MAX_TIMEeven if every single person has been infected and has recovered. Add a check somewhere that callscontext.shutdown()if there is no more work for the simulation to do. Where should this check live? - Analyze the data output by the incident reporter. Plot the number of people

with each

InfectionStatuson the same axis to see how they change over the course of the simulation. Are the curves what we expect to see given our abstract model? - Add another property that moderates the risk of infection of the individual. (Imagine, for example, people wearing face masks for an airborne illness.) Give a randomly sampled subpopulation that intervention and add a check to the transmission module to see if the person that we are attempting to infect has that property. Change the probability of infection accordingly.

Topics

Understanding Indexing in Ixa

Syntax and Best Practices

Syntax:

// For single property indexes

// Somewhere during the initialization of `context`:

context.index_property::<Person, Age>();

// For multi-indexes

// Where properties are defined:

define_multi_property!((Name, Age, Weight), Person);

// Somewhere during the initialization of `context`:

context.index_property::<Person, (Name, Age, Weight)>();Best practices:

- Index a property to improve performance of queries of that property.

- Create a multi-property index to improve performance of queries involving multiple properties.

- The cost of creating indexes is increased memory use, which can be significant for large populations. So it is best to only create indexes / multi-indexes that actually improve model performance.

- It may be best to call

context.index_property::<Entity, Propertyin the>() init()method of the module in which the property is defined, or you can put all of yourContext::index_propertycalls together in a main initialization function if you prefer. - It is not an error to call

Context::index_propertyin the middle of a running simulation or to call it twice for the same property, but it makes little sense to do so.

Property Value Storage in Ixa

To understand why some operations in Ixa are slow without an index, we need to understand how property data is stored internally and how an index provides Ixa an alternative view into that data.

In Ixa, each agent in a simulation—such as a person in a disease transmission model—is associated with a unique row of data. This data is stored in columnar form, meaning each property or field of a person (such as infection status, age, or household) is stored as its own column. This structure allows for fast and memory-efficient processing.

Let’s consider a simple example with two fields: PersonId and

InfectionStatus.

PersonId: a unique identifier for each individual, which is represented as an integer internally (e.g., 1001, 1002, 1003, …).InfectionStatus: a status value indicating whether the individual issusceptible,infected, orrecovered.

At a particular time during our simulation, we might have the following data:

PersonId | InfectionStatus |

|---|---|

| 0 | susceptible |

| 1 | infected |

| 2 | susceptible |

| 3 | recovered |

| 4 | susceptible |

| 5 | susceptible |

| 6 | infected |

| 7 | susceptible |

| 8 | infected |

| 9 | susceptible |

| 10 | recovered |

| 11 | infected |

| 12 | infected |

| 13 | infected |

| 14 | recovered |

In the default representation used by Ixa, each field is stored as a column.

Internally, however, PersonId is not stored explicitly as data. Instead, it

is implicitly defined by the row number in the columnar data structure. That

is:

- The row number acts as the unique index (

PersonId) for each individual. - The

InfectionStatusvalues are stored in a single contiguous array, where the entry at positionigives the status for the person withPersonIdequal toi.

In this default layout, accessing the infection status for a person is a simple array lookup, which is extremely fast and requires minimal memory overhead.

But suppose instead of looking up the infection status of a particular

PersonId, you wanted to look up which PersonId's were associated to a

particular infection status, say, infected. If the the property is not

indexed, Ixa has to scan through the entire column and collect all PersonId's

(row numbers) for which InfectionStatus has the value infected, and it has

to do this each and every time we run a query for that property. If we do this

frequently, all of this scanning can add up to quite a long time!

Property Index Structure

We could save a lot of time if we scanned through the InfectionStatus column

once, collected the PersonId 's for each InfectionStatus value, and just

reused this table each time we needed to do this lookup. That's all an index is!

The index for our example column of data:

InfectionStatus | List of PersonId 's |

|---|---|

susceptible | [0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9] |

infected | [1, 6, 8, 11, 12, 13] |

recovered | [3, 10, 14] |

An index in Ixa is just a map between a property value and the list of all

PersonId's having that value. Now looking up the PersonId's for a given

property value is (almost) as fast as looking up the property value for a given

PersonId.

ixa's intelligent indexing strategy

The picture we have painted of how Ixa implements indexing is necessarily a simplification. Ixa uses a lazy indexing strategy, which means if a property is never queried, then Ixa never actually does the work of computing the index. Ixa also keeps track of whether new people have been added to the simulation since the last time a query was run, so that it only has to update its index for those newly added people. These and other optimizations make Ixa's indexing very fast and memory efficient compared to the simplistic version described in this section.

The Costs of Creating an Index

There are two costs you have to pay for indexing:

- The index needs to be maintained as the simulation evolves the state of the population. Every change to any person's infection status needs to be reflected in the index. While this operation is fast for a single update, it isn't instant, and the accumulation of millions of little updates to the index can add up to a real runtime cost.

- The index uses memory. In fact, it uses more memory than the original column

of data, because it has to store both the

InfectionStatusvalues (in our example) and thePersonIdvalues, while the original column only stores theInfectionStatus(thePersonId's were implicitly the row numbers).

creating vs. maintaining an index

Suspiciously missing from this list of costs is the initial cost of scanning through the property column to create the index in the first place, but actually whether you maintain the index from the very beginning or you index it all at once doesn't matter: the sum of all the small efforts to update the index every time a person is added is equal to the cost of creating the index from scratch for an existing set of data.

We can, however, save the effort of updating the index when property values change if we wait until we actually run a query that needs to use the index before we construct the index. This is why Ixa uses a lazy indexing strategy.

Usually scanning through the whole property column is so slow relative to maintaining an index that the extra computational cost of maintaining the index is completely dwarfed by the time savings, even for infrequently queried properties. In other words, in terms of running time, an index is almost always worth it. For smaller population sizes in particular, at worst you shouldn't see a meaningful slow-down.

Memory use is a different story. In a model with tens of millions of people and many properties, you might want to be more thoughtful about which properties you index, as memory use can reach into the gigabytes. While we are in an era where tens of gigabytes of RAM is commonplace in workstations, cloud computing costs and the selection of appropriate virtual machine sizes for experiments in production recommend that we have a feel for whether we really need the resources we are using.

a query might be the wrong tool for the job

Sometimes, the best way to address a slow query in your model isn’t to add indexes, but to remove the query entirely. A common scenario is when you want to report on some aggregate statistics, for example, the total number of people having each infectiousness status. It might be much better to just track the aggregate value directly than to run a query for it every time you want to write it to a report. As usual, when it comes to performance issues, measure your specific use case to know for sure what the best strategy is.

Multi Property Indexes

To speed up queries involving multiple properties, use a multi-property index

(or multi-index for short), which indexes multiple properties jointly.

Suppose we have the properties AgeGroup and InfectionStatus, and we want to

speed up queries of these two properties:

let age_and_status = context.query_result_iterator((AgeGroup(30), InfectionStatus::Susceptible)); // BottleneckWe could index AgeGroup and InfectionStatus individually, but in this case

we can do even better with a multi-index, which treats the pairs of values

(AgeGroup, InfectionStatus) as if it were a single value. Such a multi-index

might look like this:

(AgeGroup, InfectionStatus) | PersonId's |

|---|---|

(10, susceptible) | [16, 27, 31] |

(10, infected) | [38] |

(10, recovered) | [18, 23, 29, 34, 39] |

(20, susceptible) | [12, 25, 26] |

(20, infected) | [2, 3, 9, 14, 17, 19, 28, 33] |

(20, recovered) | [13, 20, 22, 30, 37] |

(30, susceptible) | [0, 1, 11, 21] |

(30, infected) | [5, 6, 7, 10, 15, 24, 32] |

(30, recovered) | [4, 8, 35, 36] |

Ixa hides the boilerplate required for creating a multi-index with the macro

define_multi_property!:

define_multi_property!((AgeGroup, InfectionStatus), Person);Creating a multi-index does not automatically create indexes for each of the properties individually, but you can do so yourself if you wish, for example, if you had other single property queries you want to speed up.

The Benefits of Indexing - A Case Study

In the Ixa source repository you will find the births-deaths example in the

examples/ directory. You can build and run this example with the following

command:

cargo run --example births-death

Now let's edit the input.json file and change the population size to 1000:

{

"population": 1000,

"max_time": 780.0,

"seed": 123,

⋮

}

We can time how long the simulation takes to run with the time command. Here's

what the command and output look like on my machine:

$ time cargo run --example births-deaths

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.30s

Running `target/debug/examples/births-deaths`

cargo run --example births-deaths 362.55s user 1.69s system 99% cpu 6:06.35 total

For a population size of only 1000 it takes more than six minutes to run!

Let's index the InfectionStatus property. In

examples/births-deaths/src/lib.rs we add the following line somewhere in the

initialize() function:

context.index_property::<Person, InfectionStatus>();We also need to import InfectionStatus by putting

use crate::population_manager::InfectionStatus; near the top of the file. To

be fair, let's compile the example separately so we don't include the compile

time in the run time:

cargo build --example births-deaths

Now run it again:

$ time cargo run --example births-deaths

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.09s

Running `target/debug/examples/births-deaths`

cargo run --example births-deaths 5.79s user 0.07s system 97% cpu 5.990 total

From six minutes to six seconds! This kind of dramatic speedup is typical with indexes. It allows models that would otherwise struggle with a population size of 1000 to handle populations in the tens of millions.

Exercises:

- Even six seconds is an eternity for modern computer processors. Try to get this example to run with a population of 1000 in ~1 second*, two orders of magnitude faster than the unindexed version, by indexing other additional properties.

- Using only a single property index of

InfectionStatusand a single multi-index, get this example to run in ~0.5 seconds. This illustrates that it's better to index the right properties than to just index everything.

*Your timings will be different but should be roughly proportional to these.

Performance and Profiling

Indexing

Indexing properties that are queried repeatedly in your simulation can lead to dramatic speedups. It is not uncommon to see two or more orders of magnitude of improvement in some cases. It is also very simple to do.

You can index a single property, or you can index multiple properties jointly.

Just include the following method call(s) during the initialization of

context, replacing the example property names with your own:

// For single property indexes

// Somewhere during the initialization of `context`:

context.index_property::<Person, Age>();

// For multi-indexes

// Where properties are defined:

define_multi_property!((Name, Age, Weight), Person);

// Somewhere during the initialization of `context`:

context.index_property::<Person, (Name, Age, Weight)>();The cost of creating indexes is increased memory use, which can be significant for large populations. So it is best to only create indexes / multi-indexes that actually improve model performance, especially if cloud computing costs / VM sizes are an issue.

See the chapter on Indexing for full details.

Optimizing Performance with Build Profiles

Build profiles allow you to configure compiler settings for different kinds of

builds. By default, Cargo uses the dev profile, which is usually what you want

for normal development of your model but which does not perform optimization.

When you are ready to run a real experiment with your project, you will want to

use the release build profile, which does more aggressive code optimization

and disables runtime checks for numeric overflow and debug assertions. In some

cases, this can improve performance dramatically.

The

Cargo documentation for build profiles

describes many different settings you can tweak. You are not limited to Cargo's

built in profiles either. In fact, you might wish to create your own profile for

creating flame graphs, for example, as we do in the section on flame graphs

below. These settings go under [profile.release] or a custom profile like

[profile.bench] in your Cargo.toml file. For maximum execution speed,

the key trio is:

[profile.release]

opt-level = 3 # Controls the level of optimization. 3 = highest runtime speed. "s"/"z" = size-optimized.

lto = true # Link Time Optimization. Improves runtime performance by optimizing across crate boundaries.

codegen-units = 1 # Number of codegen units. Lower = better optimization. 1 enables whole-program optimization.

The Cargo documentation for build profiles describes a few more settings that can affect runtime performance, but these are the most important.

Ixa Profiling Module

For Ixa's built-in profiling (named counts, spans, and JSON output), see the Profiling Module topic.

Visualizing Execution with Flame Graphs

Samply and Flame Graph are easy to use profiling tools that generate a "flame graph" that visualizes stack traces, which allow you to see how much execution time is spent in different parts of your program. We demonstrate how to use Samply, which has better macOS support.

Install the samply tool with Cargo:

cargo install samply

For best results, build your project in both release mode and with debug

info. The easiest way to do this is to make a build profile, which we name

"profiling" below, by adding the following section to your Cargo.toml file:

[profile.profiling]

inherits = "release"

debug = true

Now when we build the project we can specify this build profile to Cargo by name:

cargo build --profile profiling

This creates your binary in target/profiling/my_project, where my_project is

standing in for the name of the project. Now run the project with samply:

samply record ./target/profiling/my_project

We can pass command line arguments as usual if we need to:

samply record ./target/profiling/my_project arg1 arg2

When execution completes, samply will open the results in a browser. The graph looks something like this:

The graph shows the "stack trace," that is, nested function calls, with a

"deeper" function call stacked on top of the function that called it, but does

not otherwise preserve chronological order of execution. Rather, the width of

the function is proportional the time spent within the function over the course

of the entire program execution. Since everything is ultimately called from your

main function, you can see main at the bottom of the pile stretching the

full width of the graph. This way of representing program execution allows you

to identify "hot spots" where your program is spending most of its time.

Using Logging to Profile Execution

For simple profiling during development, it is easy to use logging to measure how long certain operations take. This is especially useful when you want to understand the cost of specific parts of your application — like loading a large file.

cultivate good logging habits

It's good to cultivate the habit of adding trace! and debug! logging

messages to your code. You can always selectively enable or disable messages

for different parts of your program with per-module log level filters. (See

the logging module documentation for

details.)

Suppose we want to know how long it takes to load data for a large population before we start executing our simulation. We can do this with the following pattern:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::BufReader;

use std::time::Instant;

use ixa::trace;

fn load_population_data(path: &str, context: &mut Context) {

// Record the start time before we begin loading the data.

let start = Instant::now();

let file = File::open(path)?;

let mut reader = BufReader::new(file);

// .. code to load in the data goes here ...

// This line computes the time that has elapsed since `start`.

let duration = start.elapsed();

trace!("Loaded population data from {} in {:?}", path, duration);

}This pattern is especially useful to pair with a progress bar as in the next section.

Progress Bar

Provides functions to set up and update a progress bar.

A progress bar has a label, a maximum progress value, and its current progress,

which starts at zero. The maximum and current progress values are constrained to

be of type usize. However, convenience methods are provided for the common

case of a progress bar for the timeline that take f64 time values and rounds

them to nearest integers for you.

Only one progress bar can be active at a time. If you try to set a second

progress bar, the new progress bar will replace this first. This is useful if

you want to track the progress of a simulation in multiple phases. Keep in mind,

however, that if you define a timeline progress bar, the Context will try to

update it in its event loop with the current time, which might not be what you

want if you have replaced the progress bar with a new one.

Timeline Progress Bar

/// Initialize the progress bar with the maximum time until the simulation ends.

pub fn init_timeline_progress_bar(max_time: f64);

/// Updates the progress bar with the current time. Finalizes the progress bar when

/// `current_time >= max_time`.

pub fn update_timeline_progress(mut current_time: f64);Custom Progress Bar

If the timeline is not a good indication of progress for your simulation, you can set up a custom progress bar.

/// Initializes a custom progress bar with the given label and max value.

pub fn init_custom_progress_bar(label: &str, max_value: usize);

/// Updates the current value of the custom progress bar.

pub fn update_custom_progress(current_value: usize);

/// Increments the custom progress bar by 1. Use this if you don't want to keep track of the

/// current value.

pub fn increment_custom_progress();Custom Example: People Infected

Suppose you want a progress bar that tracks how much of the population has been infected (or infected and then recovered). You first initialize a custom progress bar before executing the simulation.

use crate::progress_bar::{init_custom_progress_bar};

init_custom_progress_bar("People Infected", POPULATION_SIZE);To update the progress bar, we need to listen to the infection status property change event.

use crate::progress_bar::{increment_custom_progress};

// You might already have this event defined for other purposes.

pub type InfectionStatusEvent = PropertyChangeEvent<Person, InfectionStatus>;

// This will handle the status change event, updating the progress bar

// if there is a new infection.

fn handle_infection_status_change(context: &mut Context, event: InfectionStatusEvent) {

// We only increment the progress bar when a new infection occurs.

if (InfectionStatusValue::Susceptible, InfectionStatusValue::Infected)

== (event.previous, event.current)

{

increment_custom_progress();

}

}

// Be sure to subscribe to the event when you initialize the context.

pub fn init(context: &mut Context) -> Result<(), IxaError> {

// ... other initialization code ...

context.subscribe_to_event::<InfectionStatusEvent>(handle_infection_status_change);

// ...

Ok(())

}Additional Resources

For an in-depth look at performance in Rust programming, including many advanced tools and techniques, check out The Rust Performance Book.

Profiling Module

Ixa includes a lightweight, feature-gated profiling module you can use to:

- Count named events (and compute event rates)

- Time named operations ("spans")

- Print results to the console

- Write results to a JSON file along with execution statistics

The API lives under ixa::profiling and is behind the profiling Cargo feature

(enabled by default). If you disable the feature, the API becomes a no-op so you

can leave profiling calls in your code.

Example console output

Span Label Count Duration % runtime

----------------------------------------------------------------------

load_synth_population 1 950us 792ns 0.36%

infection_attempt 1035 6ms 33us 91ns 2.28%

sample_setting 1035 3ms 66us 52ns 1.16%

get_contact 1035 1ms 135us 202ns 0.43%

schedule_next_forecasted_infection 1286 22ms 329us 102ns 8.44%

Total Measured 1385 23ms 897us 146ns 9.03%

Event Label Count Rate (per sec)

-----------------------------------------------------

property progression 36 136.05

recovery 27 102.04

accepted infection attempt 1,035 3,911.50

forecasted infection 1,286 4,860.09

Infection Forecasting Efficiency: 80.48%

Basic usage

Count an event:

use ixa::profiling::increment_named_count;

increment_named_count("forecasted infection");

increment_named_count("accepted infection attempt");Time an operation:

use ixa::profiling::{close_span, open_span};

let span = open_span("forecast loop");

// operation code here (algorithm, function call, etc.)

close_span(span); // optional; dropping the span also closes itSpans also auto-close at end of scope (RAII), which is useful for early returns:

use ixa::profiling::open_span;

fn complicated_function() {

let _span = open_span("complicated function");

// Complicated control flow here, maybe with lots of `return` points.

} // `_span` goes out of scope, automatically closed.Printing results to the console (after the simulation completes):

use ixa::profiling::print_profiling_data;

print_profiling_data();This prints spans, counts, and any computed statistics. You can also call

print_named_spans(), print_named_counts(), and print_computed_statistics()

individually.

Minimal example

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::profiling::*;

fn main() {

let mut context = Context::new();

context.add_plan(0.0, |context| {

increment_named_count("my_model:event");

{

let _span = open_span("my_model:expensive_step");

// ... do work ...

} // span auto-closes on drop

context.shutdown();

});

context.execute();

// Console output (spans, counts, computed statistics).

print_profiling_data();

// Writes JSON to: <output_dir>/<file_prefix>profiling.json

// using the same report options configuration as CSV reports.

context.write_profiling_data();

}See examples/profiling in the repository for a more complete example,

including configuring report_options() to control the output directory, file

prefix, and overwrite behavior.

Writing JSON output

ProfilingContextExt::write_profiling_data() writes a pretty JSON file to:

<output_dir>/<file_prefix>profiling.json

using the same report_options() configuration as CSV reports (directory, file

prefix, overwrite). The JSON includes:

date_timeexecution_statisticsnamed_countsnamed_spanscomputed_statistics

Example:

use std::path::PathBuf;

use ixa::prelude::*;

use ixa::profiling::ProfilingContextExt;

fn main() {

let mut context = Context::new();

context

.report_options()

.directory(PathBuf::from("./output"))

.file_prefix("run_")

.overwrite(true);

// ... run the simulation ...

context.execute();

context.write_profiling_data();

}Special names and coverage

Spans may overlap or nest. The sum of all individual span durations will not

generally equal total runtime. A special span named "Total Measured" is open

if and only if any other span is open; it tracks how much runtime is covered by

some span.

Computed statistics

You can register custom, derived metrics over collected ProfilingData using

add_computed_statistic(label, description, computer, printer). The "computer"

returns an Option (for conditionally defined statistics), and the "printer"

prints the computed value.

Computed statistics are printed by print_computed_statistics() and included in

the JSON under computed_statistics (label, description, value).

The supported computed value types are usize, i64, and f64.

API (simplified):

pub type CustomStatisticComputer<T> = Box<dyn (Fn(&ProfilingData) -> Option<T>) + Send + Sync>;